Sequence diagram style guide

Quick reference

Section titled “Quick reference”Arrows

Section titled “Arrows”- Sending - solid line

- - Replying - dashed line

-- - Sync - closed arrowhead

>> - Async - open arrowhead

)

Line breaks

Section titled “Line breaks”Add <br/> where you want a line of text to break.

GraphQL APIs

Section titled “GraphQL APIs”Use camelCase for mutation names.

Rest APIs

Section titled “Rest APIs”- Use UPPERCASE for methods

- Include both the number and description for response codes

Rule breaking

Section titled “Rule breaking”You can break a rule if:

- It eliminates ambiguity

- It makes a complex diagram more simple or straightforward

Basics

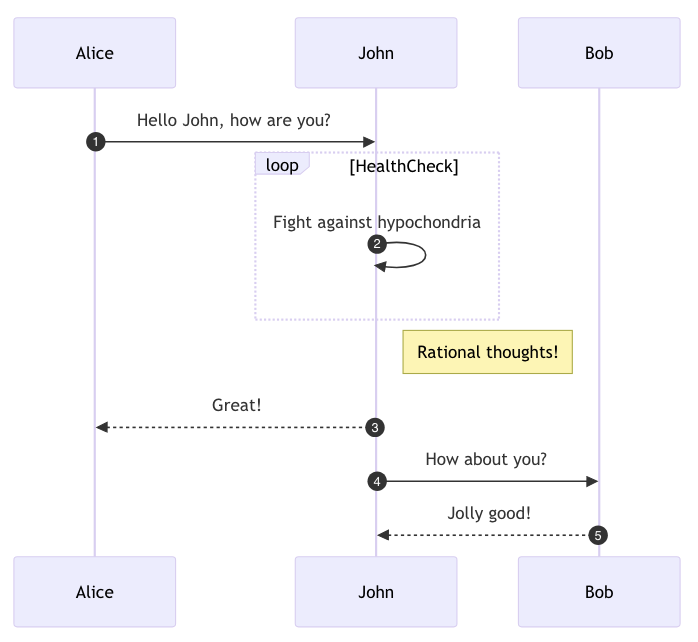

Section titled “Basics”Actor

| A human entity (for example, sender/recipient of a payment) that interacts with the system by sending or receiving messages or performing an action. An excellent example of when to depict a human is during the Open Payments interactive grant flow. Using the actor shape is optional, but if you do choose to use it, only use it with a human entity. The ordering of actors shouldn’t be arbitrary if possible. See Participant. Capitalization: Sentence case |

Participant

| A human or non-human entity that interacts with the system by sending or receiving messages. The ordering of participants shouldn’t be arbitrary if possible. Ideally, the first instance (actor/participant) in a diagram should be where the first message originates. Capitalization: Sentence case |

Lifeline

| A vertical line descending from the center-bottom of an actor or participant and represents the existence of the actor/participant over time. Used as a boundary to show the sequential events that occur to the actor/participant. |

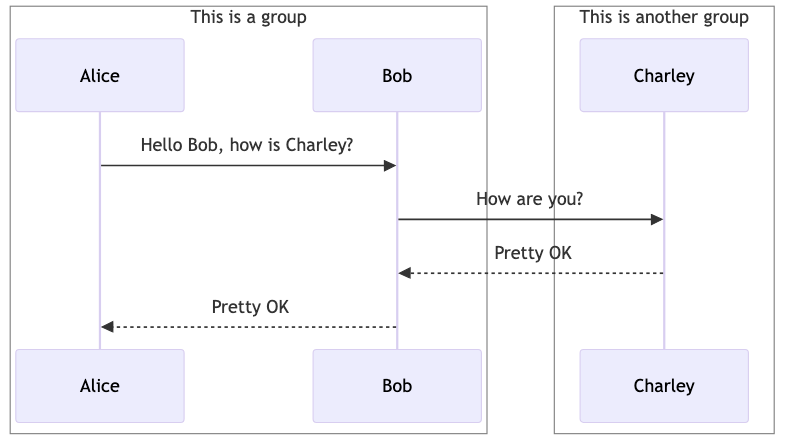

Groups

| Actors/participants can be grouped in vertical boxes. Always provide a title, in sentence case, for a group. Don’t use a group to give a diagram a border. See the Color section for additional info. |

Arrows and messages

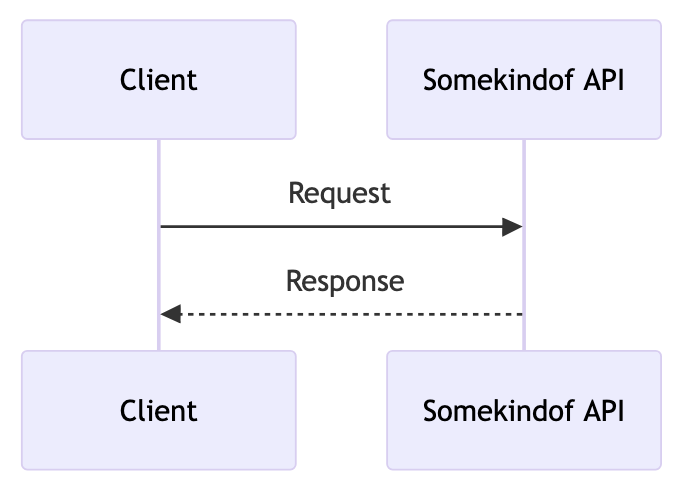

Section titled “Arrows and messages”Arrows represent messages between lifelines. The style of the arrow line and arrowhead depends on the message type.

The first message should start in the top-left corner. This means the actor/participant that’s sending the first message should be placed first in the diagram.

The left-to-right direction of the example arrows below is for illustrative purposes.

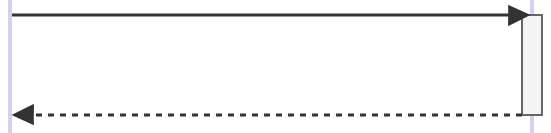

| Look | Description | Syntax |

|---|---|---|

| A synchronous message being sent (for example, an API request); the sender must wait for a response before continuing. The solid line represents “sending” and the shape of the arrowhead represents sync. | ->> |

| A synchronous message reply (for example, an API response). The dashed line represents a reply and the shape of the arrowhead represents sync. | -->> |

| An asynchronous message being sent; the sender doesn’t wait for a response and immediately continues with the next step. The solid line represents “sending” and the shape of the arrowhead represents async. | -) |

| An asynchronous message reply. The dashed line represents a reply and the shape of the arrowhead represents async. | --) |

| A bidirectional synchronous message. I don’t know when we’d use this. Note that it follows the standard syntax patterns for a dashed line and async arrowhead. | <<-->> |

| A stop/destroy message being sent. Leads to the deletion of the actor/participant or indicates the actor/participant is no longer needed. | -x |

| A stop/destroy message received. Leads to the deletion of the actor/participant or indicates the actor/participant is no longer needed. | --x |

| A self-message; a recursive call. Note that it follows the standard syntax patterns for sending/replying and sync/async. | ->> |

Lines without arrowheads

Section titled “Lines without arrowheads”Mermaid supports solid and dashed lines without arrowheads. In general, we should save these as a last resort. Think about why you want to include the line, then see if there’s some other way to show the information (for example, note).

One example of an arrowless line is in the OP Client Keys diagram: https://openpayments.dev/introduction/client-keys/#sequence-diagram

After Step 1, there’s a line from the client to the resource server to show that Step 1 also “somehow” links to the resource server, since that’s where the keys are stored. But this isn’t a particular OP API call. It’s just something that an ASE would do (upload the keys to be available from the RS). In other words, a 🪄step.

Adding text to messages

Section titled “Adding text to messages”Every message should have descriptive text even if you think it’s obvious what the messages represent. It doesn’t need to be a novel.

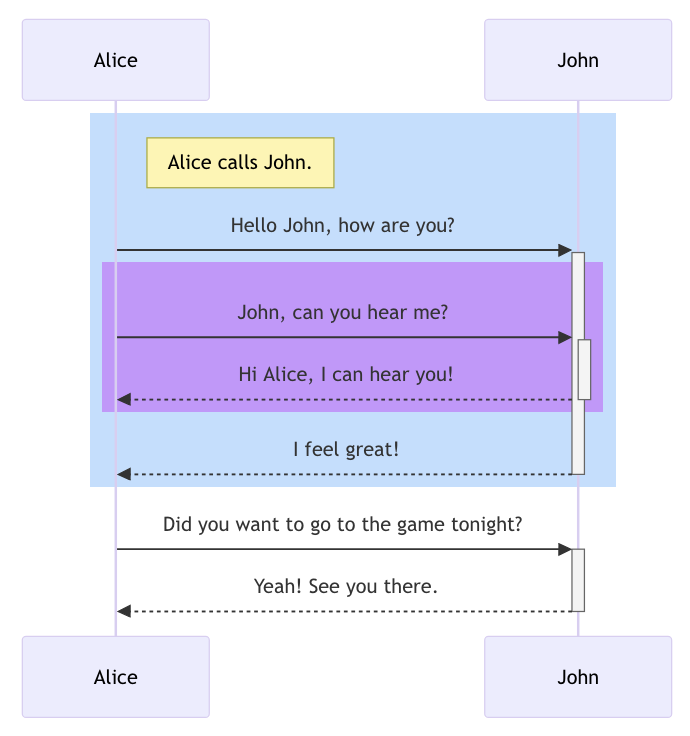

A simple example…

| Good | Bad |

|---|---|

|  |

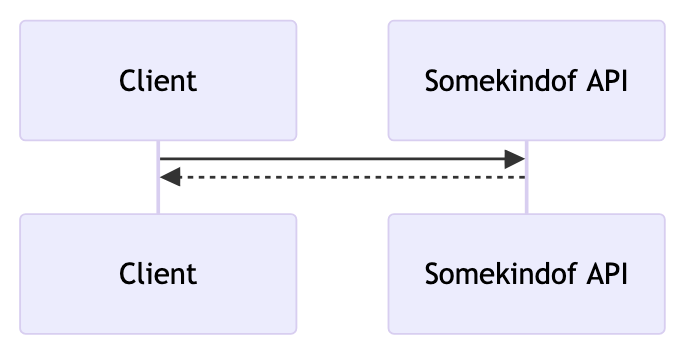

Depending on how wide the sequence diagram is, or the information you’re conveying, you might need to add line breaks to text. This will make the diagram more narrow (so it fits better in Starlight’s content frame) and increase the font size, making the diagram more readable.

Compare:

| Line breaks | No line breaks |

|---|---|

|  |

Formatting code

Section titled “Formatting code”Mermaid doesn’t allow you to format text using a code-like font.

If you think the text needs to stand out in some way, you could use:

- Single or double quotes

- Square or curly brackets

- Line breaks

- A combination of what’s above

Instead of prescribing specific formatting, the most important thing is to remain as consistent as possible both in a single message and a single diagram.

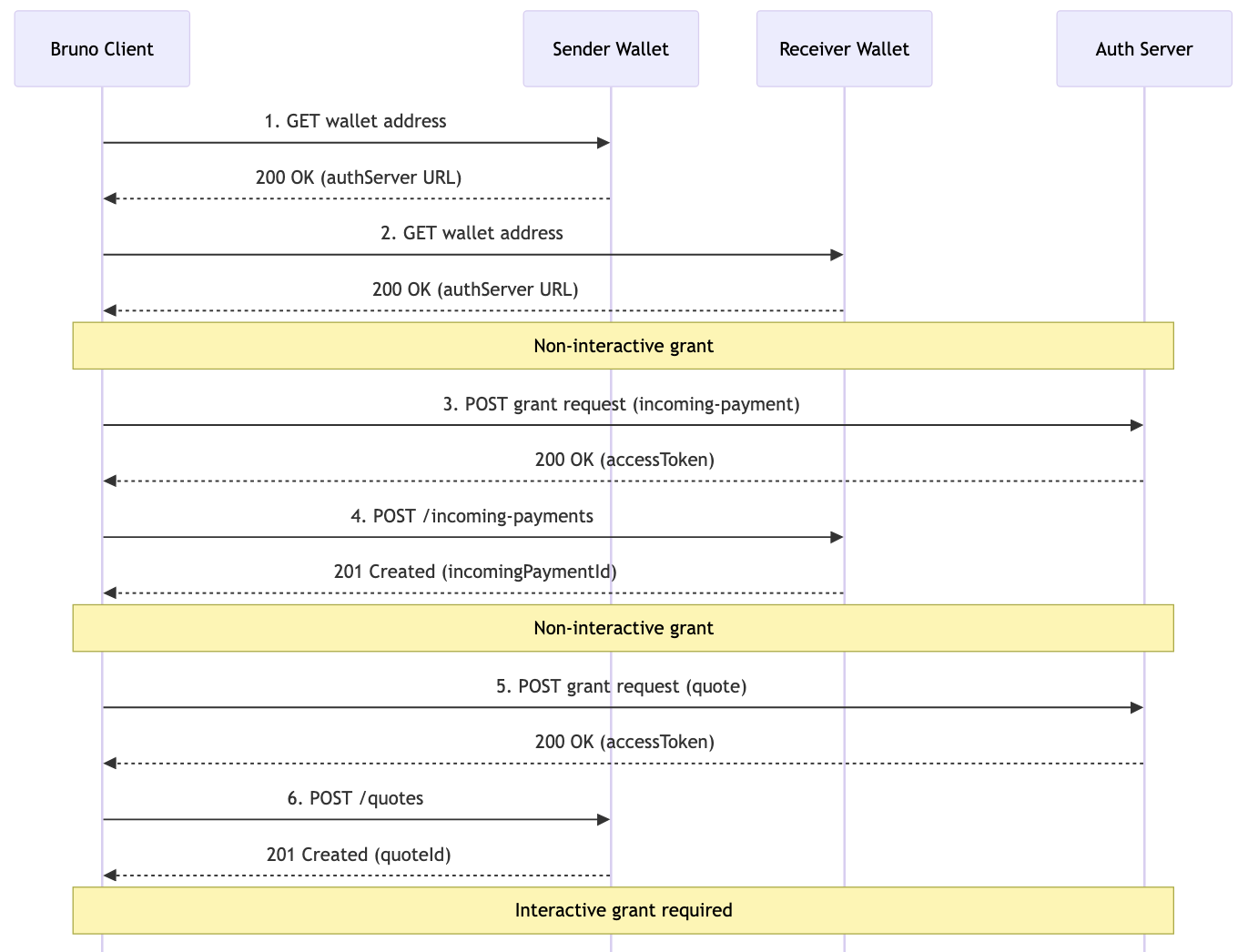

Formatting REST APIs

Section titled “Formatting REST APIs”Methods

Section titled “Methods”If including the method in the request, include the method in uppercase at the beginning of the description.

- ✅ GET wallet address

- ❌ Grant request (POST)

- ✅ Get incoming and outgoing wallet addresses

What follows the method is up to you. Any of these are OK:

- GET wallet address url

- POST make initial grant request

- POST /incoming-payments

- GET {client_domain/jwks.json}

Response codes

Section titled “Response codes”If including the response number, include the number at the beginning of the description, followed by either the HTTP response code description or the Open Payments description, whichever is more descriptive.

- ✅ 200 OK

- ✅ 200 wallet address found

- ❌ Incoming payment not found (404)

Formatting GraphQL APIs

Section titled “Formatting GraphQL APIs”API names

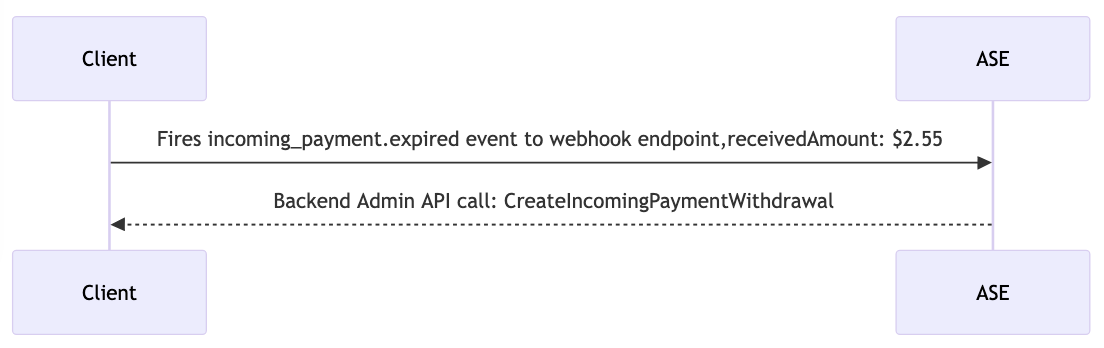

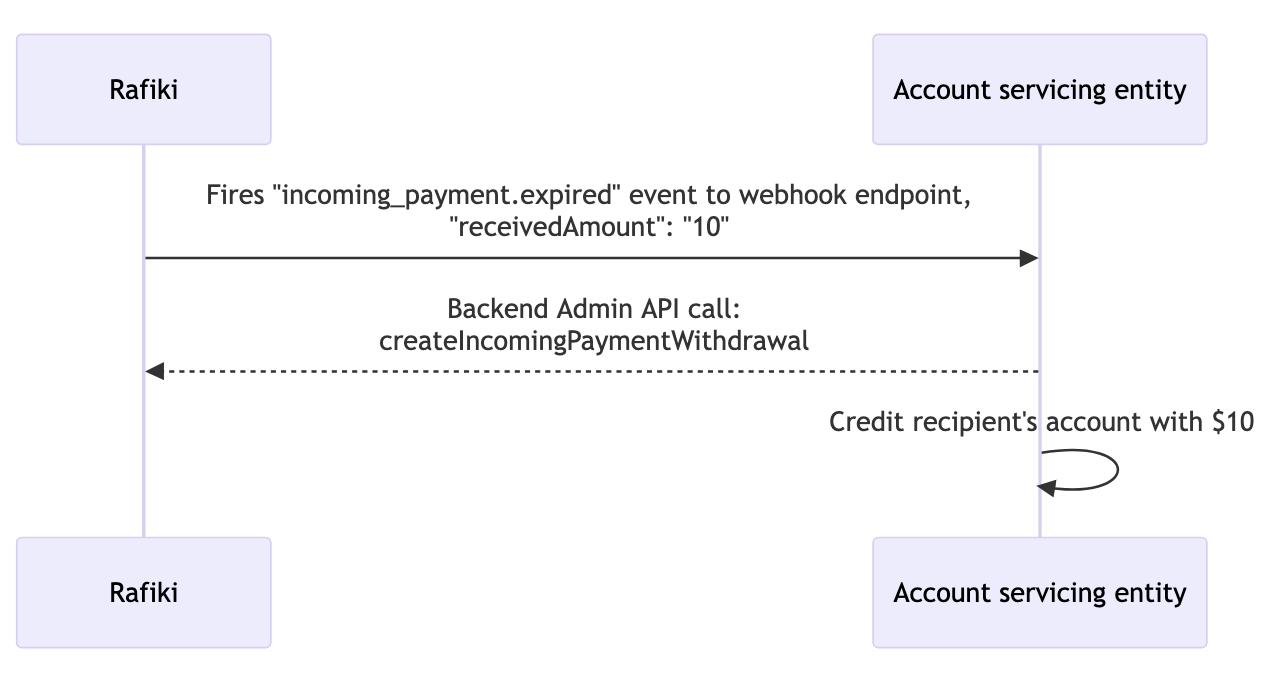

Section titled “API names”Rafiki currently has two GraphQL APIs: the Backend Admin API and the Auth Admin API. Since they’re both “admin” APIs, it’s important that we write out the API name completely, so readers know which API we’re discussing. Capitalize each word.

We don’t have many (any?) sequence diagrams in the Rafiki docs outside the webhook events page. I don’t know if there are any instances where we’d include the API name but not include a specific mutation.

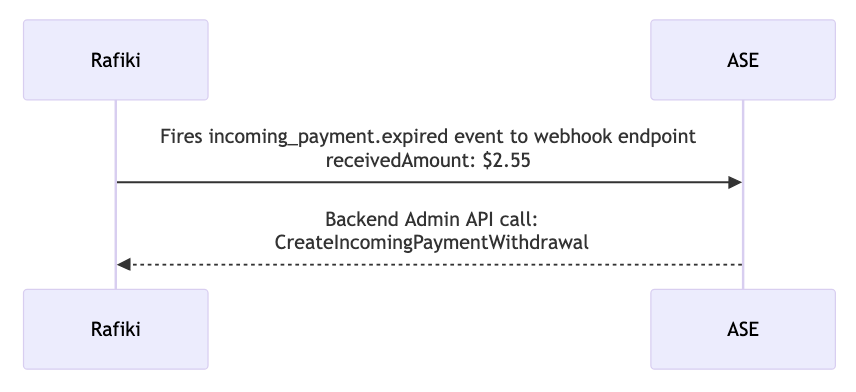

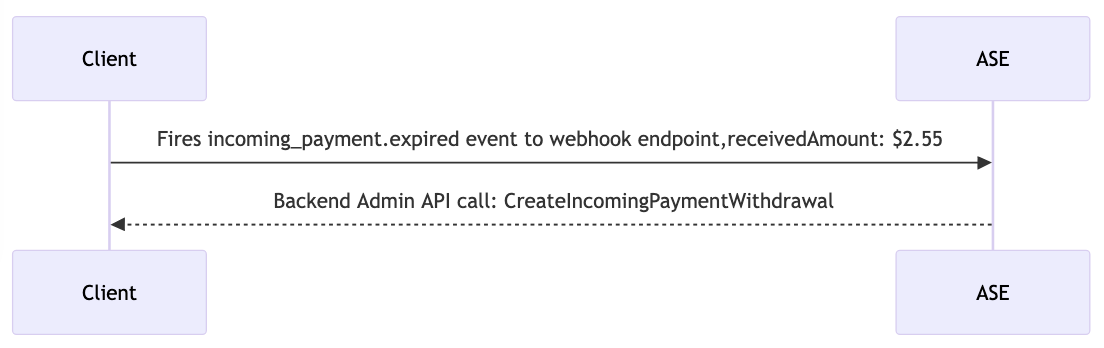

Mutations

Section titled “Mutations”Write mutations in camelCase.

At this time, we don’t need styles like these:

- Follow each API name with call: and the mutation in camelCase

- Always include both the API name and the mutation

This example shows the previous points applied to the response. This way you can get an idea about what it would look like should we make them a standard.

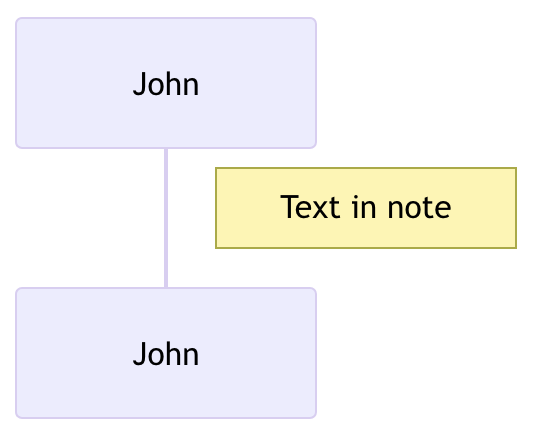

Mermaid allows you to place notes to the right of, the left of, and over an actor/participant. They can also span multiple actors/participants.

Notes have a yellow background that you can’t change.

Occasionally, you might want to call out and section off portions of a diagram. Groups aren’t appropriate because they stretch vertically. A background color might be distracting or make the diagram too busy. And the information might not be an operator.

In this case, it might be a good idea to use a note that spans over multiple participants as a way to call out and section off information.

Sequence numbers

Section titled “Sequence numbers”Using autonumber, you can have Mermaid attach a sequence number to each message in a diagram. This includes messages without arrowheads. You can’t change their styling.

sequenceDiagram autonumber Alice->>John: etc…The more complex a sequence diagram is, the more likely it is that adding sequence numbers will help with clarity. Use your best judgement. A diagram with 2 - 4 messages probably doesn’t need numbering.

Activations

Section titled “Activations” | An activation represents the time during which a participant is performing an action. The longer the task will take, the longer the activation box will be. Examples include polling and showing how long a connection persists. When including an activation, always have a reply message for clarity. Activations can be stacked. |

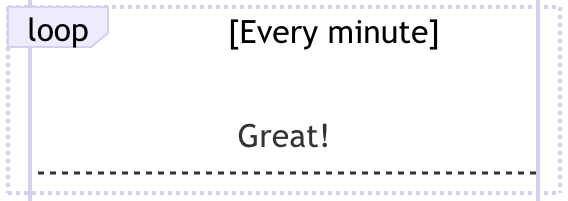

Interaction operators

Section titled “Interaction operators”An interaction operator is a container that groups interaction fragments. Containers are all formatted the same way, with the notation appearing in the top-left.

Titles are optional but strongly recommended. Titles appear centered at the top and enclosed in brackets.

Use operators intentionally and not as a way to draw a box around something.

Some, if not all, operators can be nested.

| Notation | Description |

|---|---|

alt | Alternative An if-then or if-then-else process or interaction. Symbolizes a choice between two or more message sequences. |

opt | Option An if process or interaction. The process only occurs if a certain condition is met. |

loop | Loop A basic repeating interaction. |

par | Parallel Shows actions are happening in parallel; shows interactions running concurrently with each other. |

critical | Critical region Indicates that the fragment can only have one thread that it runs at any time. The fragment must complete before another thread can run. Shows actions that must happen automatically with conditional handling of circumstances. |

break | Break Indicates a stop of the sequence in the flow, usually to model exceptions. The sequence breaks/stops/doesn’t perform any of the remaining sequence and does what’s defined in the operator instead. Breaks only cause the exiting of an enclosed interaction’s sequence and not necessarily the entire sequence depicted in the diagram. In cases where a break combination is part of an alt or loop, then only the alt or loop is exited. |

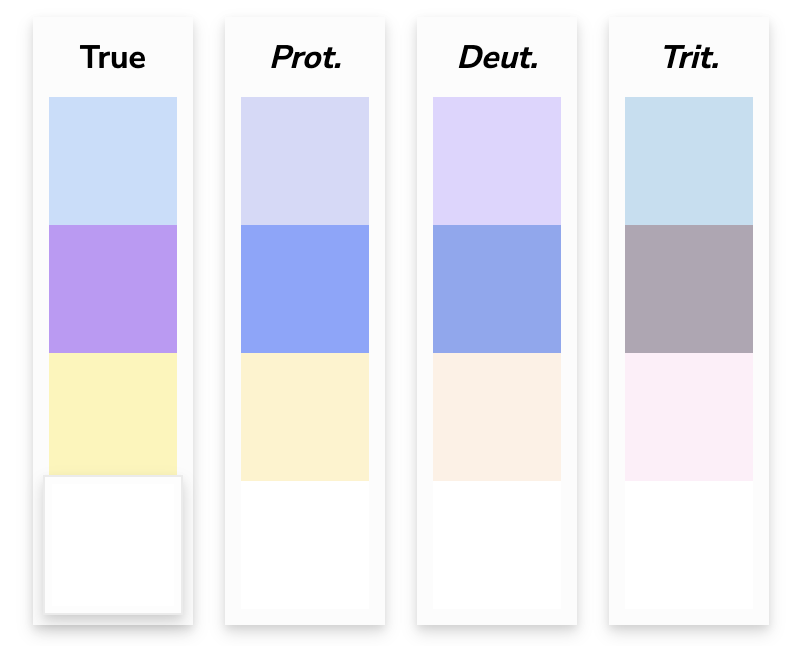

Colors

Section titled “Colors”You can change the background color of groups and, separately, through background highlighting. Color can be added using RGB values.

Also remember that using spanning Notes is a way to call out and section off information. Notes have a yellow background color that can’t be changed.

Best practices when it comes to using color:

- Use color sparingly. Think about why you want to use colors. Groups have transparent backgrounds by default. The border around the group is probably enough to call attention to the contents in the group.

- Use color consistently in a single diagram.

- Check the contrast between color(s) and text. Make sure the text is still legible.

- Consider color blindness when selecting colors–especially if they overlap. Difficulties distinguishing between red and green is the most common type of color blindness. Coloring for Colorblindness is one of many tools that can help you see how colors may appear to others.

The following example color palette uses a few ILF-flavored colors as the True colors and shows how these colors will appear to someone with colorblindness (depending on the type).

- Check the diagram on multiple screens if you have them (for example, laptop/desktop monitor). A light color on one monitor, for example, might look significantly darker on another.

- Check the diagram in light and dark mode. If you add color to a diagram, check that the diagram is legible in light and dark mode. It probably will be because I think Mermaid keeps the background white. It’s still a good habit to get into. Even if a diagram is legible in dark mode, for example, the contrast between the dark UI, the white diagram background, and a light background highlight color might be a bit harsh on the eyes.

Regardless of how nice you think the following diagram looks, the use of colors checks most of the boxes. I’d argue that the purple is pushing it when it comes to text contrast/legibility.